Sometimes, we treat money with emotional consequences. Why? What is this cognitive bias and how can marketers and merchandisers facilitate decision-making instead?

Sometimes, we treat money with emotional consequences. Why? What is this cognitive bias and how can marketers and merchandisers facilitate decision-making instead?

The other day, the Crobox team was skiing in the Austrian Alps.

We ordered lunch up in the mountains – and spent more on food than we would normally.

Our response?

“We’re skiing so we can and should spend more on food!”

Rationalizing spending in this way is actually emotional, and part of a cognitive bias called mental accounting. Throughout this article, I’ll cover mental accounting theory through the lens of behavioral psychology.

To see how this works in practice, I’ll show examples of mental accounting in eCommerce. We’ll also go through why this is important.

But that’s an easy question to answer: Shopping is a uniquely personal experience. Yet there are a wealth of biases that consumers leverage to make choices and decisions.

If you can understand how your shoppers make these decisions across your funnel, you can not only prime these decisions, but make shopping a whole lot more seamless, intuitive, and fun.

Because spending money isn’t always a fun choice. But, as a webshop or retailer at the receiving end of this, you’ll want to make the decision-making process better.

A no-brainer, right? Good, let’s get started.

Mental accounting is the practice of sorting spending and finances into mental buckets or categories.

Making these buckets imaginary. Where things like ‘health’ spending take precedence for some, for others ‘vacation’ or ‘leisure’ make up more of the mental spending.

But it’s not often a conscious choice to put money into one bucket or another.

Take the skiing example. You might be more likely to spend because you’re on vacation. Hence, the mental bucket: “Leisure”.

But when you’re back home, would you justify spending the same amount on a meal in the Alps as you would in your hometown?

Probably not.

Throwing in some 1970s ski ballet for your pleasure.

And if that’s the case, how rational is this spending of money?

At its core, money is fungible. Meaning, it’s made up of units that are all interchangeable and indistinguishable from one another. In mental accounting, we actually begin to treat money as less fungible than it is.

That’s why mental accounting is a mental bias. It’s a shortcut our brain uses to justify how we treat and spend money.

We can’t exactly rationalize spending the same amount of money on eating out in two different contexts, even if we think it’s a rational decision.

In short, mental accounting describes the behavior of treating money differently as you mentally categorize it based on its source or intent.

According to studies by Prelec and Simester (2001), people are more likely to spend more when they pay with a credit card than cash. Willingness to pay will always depend on context.

Willingness to pay (WTP) is the maximum price a customer is willing to pay for a product or service. It’s typically represented as a price range.

In mental accounting theory, people assign meaning to money. This is a result of some psychological principles you may have heard of before.

Part of mental accounting relies on the sunk cost fallacy. This describes the behavior where individuals are more likely to follow through with something if they have already invested time, effort, or money into it (think of the Endowment Effect bias).

For example, let’s say you paid for a cinema ticket. But, at the last minute, the movie you wanted to see gets canceled.

Will you more likely:

According to Kahneman and Tversky (1984), more people will go for the second option to avoid the sunk cost fallacy, although they may end up spending double in one night.

That’s because once an individual has committed to something – like seeing a movie – they will be more inclined to do anything in their power to see it through rather than avoid loss or disappointment.

Loss aversion is the psychological observation that human beings experience losing something as worse than gaining something else. This means many will not see a loss as equivalent to gain.

Think about this next time you’re standing in a way too long line but are too stubborn to leave (hey there, irrational consumer).

But this behavior also comes at the expense (pun intended) of spending time and, where mental accounting is concerned, money.

In fact, in Kahneman and Tversky’s study, they found that a lost ticket had the same value as lost cash, but nearly twice as many people were willing to ignore the lost cash but not the lost ticket.

“As humans, we are loss averse: We want to avoid losses wherever possible, and losses are perceived to be more powerful than equal gains.” (Source).

Imagine you’re at a club. You go to tie your shoe and kneel on a $100 bill.

I know, I know, we should all be so lucky.

What behavior do you think you’ll carry out?

If you’re more like person A then chapeau.

But if you’re like me – and a lot of other people I know – then you’ll likely assign a different meaning to the $100, although the value of the money itself never changes.

Windfall gains are an unexpected increase in income. Like receiving an inheritance, or winning the lottery. This gain will go into a different mental bucket with a different value assigned to it than if you had earned the money yourself.

The same theory can be applied to the behavior of drinking coffee every day – again, guilty!

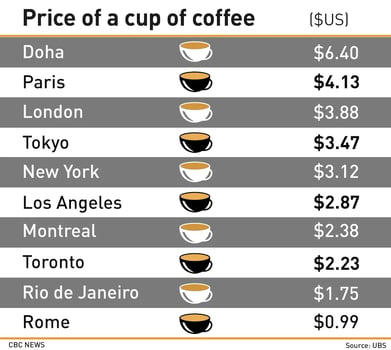

Will you think twice about spending more on coffee in London than in Rome?

You don’t think twice about the money you spend on buying a coffee. However, when looking to purchase a necklace for the same price as your daily coffee for a month, you might do a double-take.

This kind of budgeting is based on emotional factors, not rational ones.

Thaler, 1895, as documented by Gupta and Kim (2009).

Mental accounting, like many other psychological marketing principles, is all about framing and context.

Think of this context. You’re buying beer from:

Where will you be more likely to justify paying a higher price point? Most likely at a fancy hotel, right? In general, hotels can justify charging more. Just like airports, or ski resorts.

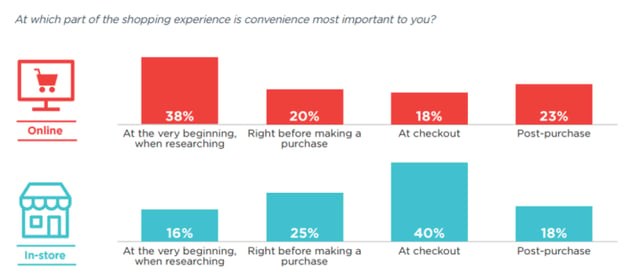

Context here is key. Which is where you step in as a retail marketer. And framing is imperative for you merchandisers out there.

At the end of the day, consumers perceive gains and losses differently, depending on how the purchases are framed. This is why mental accounting is so powerful when selling your retail products.

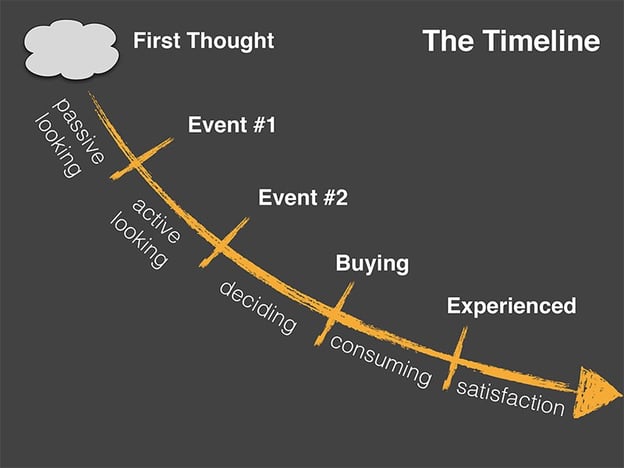

Your shoppers are drowning in choice overload. They struggle to make quick decisions on your webshop. Which can easily cause bounce, dissatisfaction, or urge them to shop elsewhere.

If you can understand mental accounting, you can start leveraging nudges at different parts of your webshop to streamline these quick decisions.

For instance, price anchoring, product recommendations, or offering free shipping at checkout are nudges that will tap into the mental accounting bias and help streamline choices. We’ll discuss a few of these later on.

For more on how shoppers make decisions across the eCommerce funnel, read our decision science and product discovery ebook.

This is a big one: Consumers can experience unpleasant feelings when they spend money. Related to being loss averse, giving money up can be a tough pill to swallow.

‘Transactional utility’ is a term to describe the happiness a customer gets from the perceived value of the deal…It’s said to be the difference between the actual price and the reference price (Source).

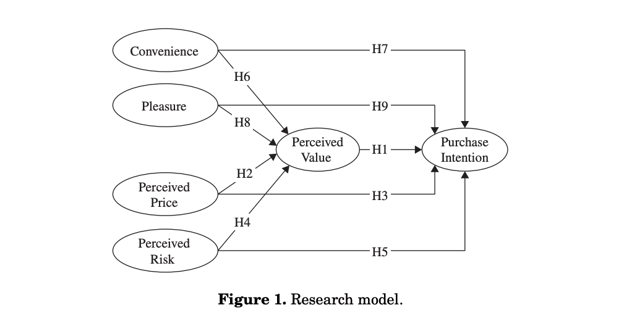

To see what people spend money on is one thing. But understanding the core of why they spend money on what they do to optimize the path to purchase.

Especially for eCommerce. On your digital channels, the pain of paying is higher. Customers can’t interact with your products in the same way they do in-store. Meaning, the transactional utility could decrease.

Understanding mental accounting will help you alleviate this pain, supporting the decision to pay in the most seamless and frictionless way.

Understanding mental accounting is important because you will show your customers you care about how and why they make purchases.

In a world where brands are shifting from commerce to content, and from pushing products to selling experiences in context, this is key.

Seeing behavior in context in this way will not only help you create better marketing and merchandising strategies but allow you to understand your shopper’s decision-making frameworks.

And, therein, their psychographics. In other words, the psychological drivers behind their purchase intentions and shopping states.

For more on this topic, psychographic segmentation is how retailers can go above and beyond for personalization, while still staying within data-protection laws (like the GDPR in Europe).

Offering gift cards instead of cash is one way to promote mental accounting in a way that benefits both the customer and your brand.

Gift cards can lead one to “regard, allocate, and consume these funds differently than if the gift is given as cash” (White, 2008).

Remember that in mental accounting, we treat money as less ‘fungible’ than it is. Instead, assigning emotional value as currency.

Offering gift cards is a way to make the payment easier, already bucketing the purchase for the shopper so that they don’t go through the cognitive pressure of doing this themselves.

Best practices for offering gift cards for mental accounting:

“Across four experiments, the presentation of a gift card rather than cash led to both intended and actual spending beyond the amount of the original gift, and also influenced the types of purchases that customers made” (White, 2008)

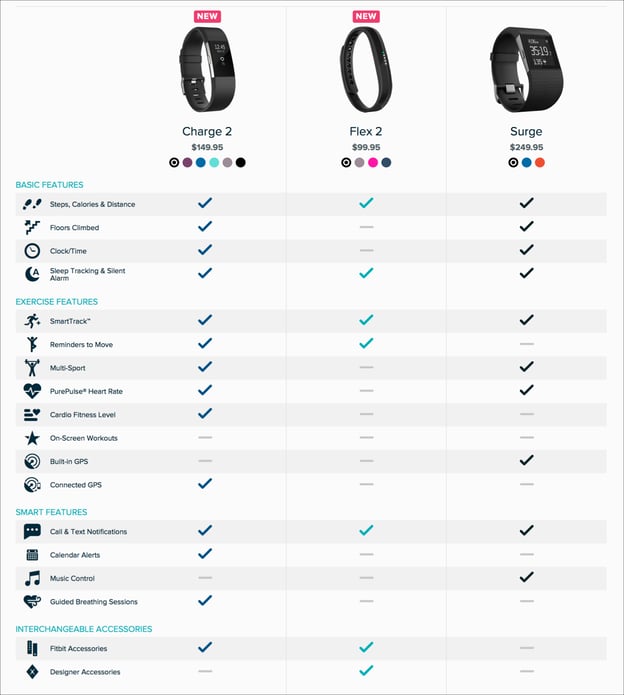

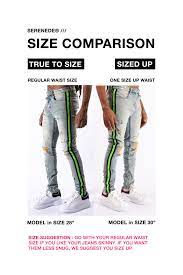

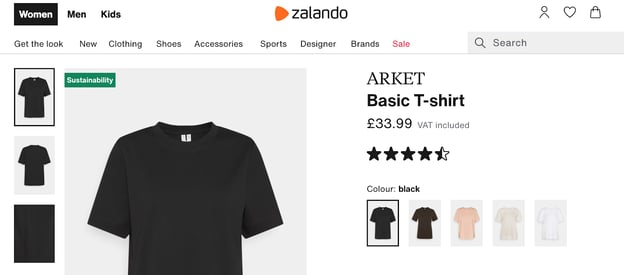

Imagine you’re selling two options for a pair of jeans. But one is more expensive than the other. Your shoppers will most likely opt for the cheaper pair, right?

But what if you had information that the more expensive option was made from sustainable materials?

Eco-conscious shoppers may be more likely to opt for this one instead. A product comparison tool can suddenly move a product from the mental bucket ‘expensive hedonic’ to ‘expensive but good-for-the-planet’.

Having product comparisons on your product detail page will make that information available straight away to the customer, facilitating their mental accounting.

Product comparison best practices for mental accounting:

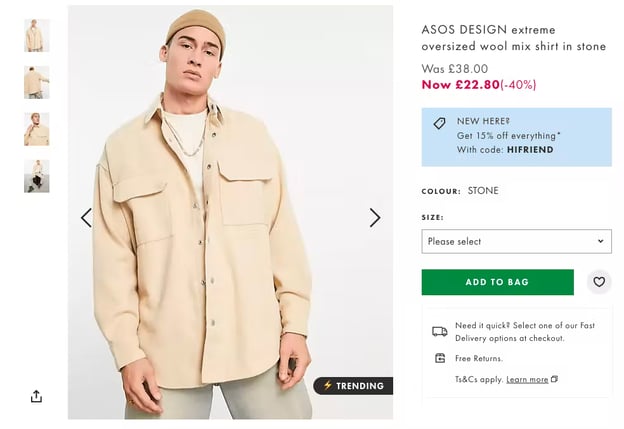

Price anchoring suggests one price to your customers while crossing out the previous price. This anchors your customer’s knowledge on the price already suggested.

Which will help mental accounting because it gives clear pricing information to the shopper to make a more informed product choice.

Psychological pricing is a great way to tap into mental accounting. Think about other principles like the Decoy Effect, Price Differentiation, and number designs.

Plus, remember how important framing is?

To understand how and where to place your prices on your lister or detail pages, check out our ebook on persuasive UX design.

Psychological pricing best practices for mental accounting:

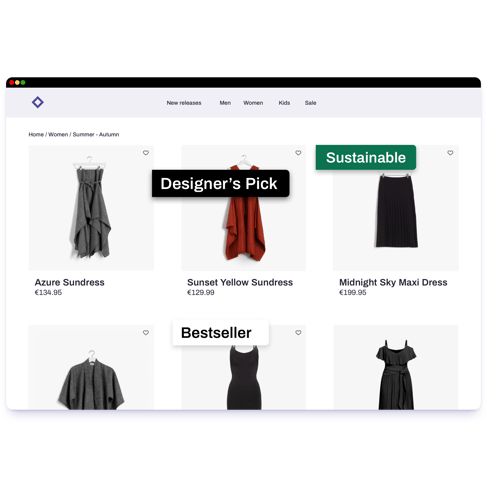

According to Wu, Day, and MacKay (1988), distinguishing between attributes and benefits offers opportunities to study consumer preferences.

In other words, separating attributes from benefits on your webshop will help you understand which promotional messages drive purchase behavior. For instance,

To facilitate decision-making with mental accounting as the basis, you should be combining your attributes and benefits.

I.e.,

I’ll answer that for you right now: You should test your product badges. At Crobox, we can auto-optimize these based on the individual’s context. So the message your shopper sees is personalized to their needs, wants, and (of course) their mental accounting process.

For example, if a “bamboo” (attribute) shirt is also “good for the environment” (benefit), this product information will facilitate mental accounting and ease the final purchase decision.

Best practices for selling attributes as benefits for mental accounting:

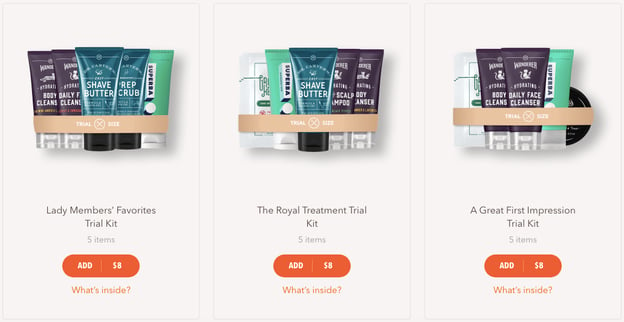

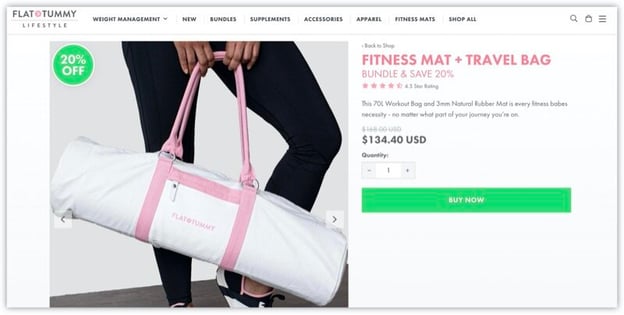

When you sell two or more products together at a discounted price, this is called product bundling. For instance, things like:

Product bundling facilitates mental accounting for the consumer. You are combining categories (and cross and up-selling too) so that they don’t have to make these choices themselves.

Buying a travel bag for your fitness mat might seem like an unnecessary, additional purchase. But, buying both together (fitness mat + travel bag) makes sense.

Shoppers will appreciate a bundling strategy if you provide a smart combination of similar products. But they will also see this as an offer, so it’s important you discount the overall price.

Product bundling best practices for mental accounting:

Understanding mental accounting will go a long way. Not only is the pain of paying the biggest bottleneck for the majority of retail shoppers, but choice overload is the market’s biggest foe.

Facilitating purchase decisions will:

These, combined with understanding how your customers spend money, will get you closer to your customers.

That’s why psychology is so key, and the cognitive biases and theory that go with it, are so important.