Throughout the history of marketing, our understanding of consumer behavior has shifted from rational to irritation.

Throughout the history of marketing, our understanding of consumer behavior has shifted from rational to irritation.

If you’re as much of a science fiction fan as yours truly, you’ve probably recognized the legend in the banner image above as the late Leonard Nimoy in his role as Spock from the original Star Trek tv-series.

As you may know, Spock is known for his impeccable logic and analytical skills. He comes from a species that takes pride in solving their problems solely on rationale, with as little interference from emotions as possible.

This makes Spock the ideal counterpart for the series protagonist, captain James T. Kirk; a brash and adventurous commander, who relies more on his feelings and gut instinct.

All in all, the duo serves as an excellent analogy for (the lack of) rationality in consumer psychology. When it comes to making financial decisions, we’d all like to think of ourselves as Spocks: smart thinkers who are easily capable of deducting the best option from a set of alternatives.

In reality, however, we’re a lot more like Kirk. Throughout the years, behavioral science has taught us that our preferences and decision-making abilities are nowhere near as stable as we’d like them to be, causing a small revolution in marketing and sales departments.

Stage left: Enter Behavioral Economics.

This article will chart how psychology has transformed the consumer throughout the years from rational to irrational, from which study of behavioral economics was born.

Without further ado, it's time to embrace the inner Kirk by of your customers by debunking the myth of the rational consumer with the fundaments of behavioral economics.

First, let's go back in time to understand the transition that practitioners and academics went through from the rational to irrational consumer.

Most economists credit the foundation of the rational consumer to the great Scottish philosopher Adam Smith. In his 1759 book, The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Smith discussed the idea of the "Homo Economicus," as the self-interested consumer with a shrewd mindset of a seasoned economist.

Adam Smith (1723-1790)

Adam Smith (1723-1790)

There are several characteristics to the Homo Economicus:

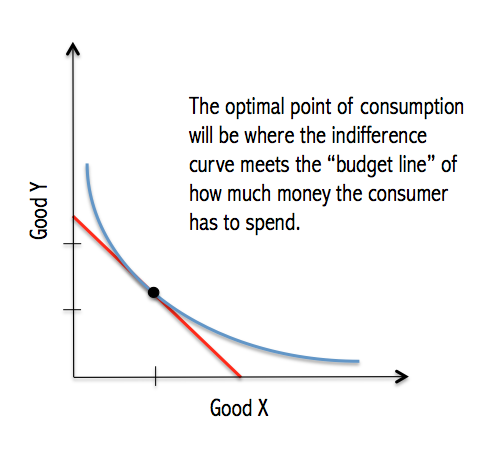

For a long time, the above description served as a hypothetical model for consumers, and neoclassical economists used this to predict business. A well-known example for this is the indifference curve.

Let’s say you have the choice between two products, apples and oranges. The idea is that the more you consume of either one, the lower the amount of satisfaction you’ll get from it.

In this graph, the blue line represents all the different possible proportions between the two products that will give you the same level of satisfaction.

By adding a budget line - the red line indicates how much of each product a person can buy with how much they have to spend so "budget line" - economists are able to pinpoint the exact point of optimal consumption: the point where you're able to buy the most satisfaction with your money.

Consumer spending was therefore rationalized as such. Which sounds great and easy, but unfortunately offered both a simplistic and idealistic perspective of consumers.

We might like to believe that we’re always capable of making the right decisions, but there are dozens of biases and other influences that prevent us from doing so.

Throughout the years, many scientists and philosophers - Solomon Asch, Daniel Kahneman, Amos Tversky, Richard Thaler, Dan Ariely, Thorstein Veblen, John Maynard Keynes, just to name a few - voiced their criticisms about the idea of a Homo Economicus.

Many made breakthrough discoveries that slowly but surely tore apart the image of the “rational consumer” and birthed the concept of "behavioral economics". In fact, both Daniel Kahneman and Richard Thaler have won Nobel Peace prizes.

Behavioral economics applies psychological insights in order to understand and influence behavior in the economy. This thus debunks the rational consumer and nuances the Homo Economicus paradigm.

What behavioral economics proposed is that we are not rational consumers. We are not Spoks (aliens), but Kirks (human), and so this new economic and psychological theory began to make sense.

Our cognitive responses factor in intuition, emotion, color, norms, availability, and a whole host of other biases that make it next to impossible to make a 100% rational purchase decision instantaneously!

In line with this, Thaler investigates Nudges: small changes in how options are presented to us. Most consumers are unaware of these nudges. Accordingly, where we attributed a rational choice to something, it's possible that an incidental cue (or nudge) affects this choice and is therefore more irrational.

For Kahneman too, choices are always grounded in a cognitive process that is teeming with biases, habits, contradictions, and psychological nuances. After all, we are only human, and this is why we have irrational minds.

Initially, this new ideology of behavioral economics and the irrational consumer wasn’t met with much enthusiasm within the commercial industry.

British filmmaker Adam Curtis wrote an interesting piece about the clash between traditional advertisers and acolytes of psychology during the '50s and '60s. In the article, both opposing camps championed two different approaches.

On the one hand, traditional advertisers were fierce advocates of the Unique Selling Proposition: highlighting a specific benefit of a product to set it apart from the opposition.

The new wave of psychologists, on the other hand, favored in-depth research into the (largely) subconscious motivations of the consumer and leaned towards strategizing on empathy rather than detailed qualities.

This tension is something we see in the hit-tv-show Mad Men. From the first episode, Don Draper throws away a document of psychological insights to help him sell tobacco. He decides to go with highlighting the USP of tobacco instead: it's "roasted" quality.

In the season's finale, however, things come full-circle. Look at his genius pitch for Kodak’s new projector in aptly entitled episode, "The Wheel":

Moving from USP to psychology, Draper sweeps all the technical qualities of the product (the projector) aside, building his case solely on the emotional benefits for the consumer. The rigid image of the rational consumer was debunked, making place for a fresh perspective.

So now that you’ve heard the history, let’s discuss the science. Naturally, there are countless factors that can influence a person’s decisions, both internally and externally.

To make things a bit more structured, I've summarized some of the cornerstones to irrational consumerism into three themes that are also observed in behavioral economics:

1. Emotions

2. Context

3. Time

Emotions have long been known to shape our choices in many ways. We use cognitive appraisal to anticipate the emotions we expect with an upcoming (purchase) decision. Though that may sound like a rational thing to do, not all appraisals are.

For instance, anticipating guilt can be good when you’re on a diet and craving some chocolate. But anticipating fear might scare you out of doing things you want to do - such as stopping people who are afraid of flying from going on vacation by plane.

The connections between decisions and emotions are so strong that they even defy logic. Just consider the fact that accidents are more likely to happen by car, yet this doesn’t dissuade individuals from using them.

But that's not all.

Consumption by itself can also be a means to an end when it comes to regulating our emotions or affirming our self-image by buying status goods.

Just think about it:

Did I really have to order takeout after that tough day at work? Did I really have to buy those expensive new clothes?

Your rational self might disagree, but your emotions are telling you: “Go ahead, you deserve this right now.”

Pro-tip for marketers: Create stronger messages for your audience by finding the right emotional appeal.

Using humor in advertisements has shown to not only increase people’s opinion of a brand, but also helps them to remember the brand better.

Anticipated regret, on the other hand, can be quite a powerful tool as well, convincing shoppers to act faster. Displaying prompts on a product page that say “Don’t wait too long, only a few items left!” is likely to trigger a person’s fear of missing out.

In this case, consumers will suddenly feel the urge to quickly finish their transaction, as they don’t want to feel disappointed if the item is sold out.

Most decisions are context-specific, meaning they are influenced by situational factors. This can relate to anything ranging from environment, past decisions, alternative options, etc.

In particular, the phrasing of a message is known to greatly affect a person’s preferences - as established in Tversky’s and Kahneman’s famous experiment on psychological framing.

In this study, people were presented with a hypothetical scenario in which a group of 600 people were caught with the outbreak of a deadly disease and asked to choose between two possible solutions. Most people preferred saving 200 people for sure, rather than taking a 33% chance of saving everyone (with a 66% that all would die).

However, putting these options in a negative frame significantly changed people’s preferences. Suddenly, the 33% that no-one would die (with a 66% that everyone would) seemed more preferable than a guarantee that 400 people would die.

Conclusion: people act risk-averse when there are things to gain, but risk-seeking when there’s something to lose - even when the effective outcome of both options is the same.

When you offer a basic and a premium package in your store and you want more people to choose the second option, you might try making use of the decoy effect.

Adding a third option that is similar in price to the premium option, but offers significantly less advantages, will automatically make the premium option seem more attractive.

Decoy effect: suddenly $7 popcorn seems pretty reasonable, right?

Decoy effect: suddenly $7 popcorn seems pretty reasonable, right?

Pro-tip for marketers: Build your website in such a way that it helps visitors to make up their mind.

On a more general note, you might also want to reduce choice overload to make the process of selecting a product easier. A good way to do this is by displaying product tags like "Most popular," "Just added," or "Our top pick" on your overview page.

Lastly, consumer behavior is not just irrational between emotions and situations, but also across different moments in time. As consumers, we often find ourselves faced with intertemporal choices. These are decisions in which the moment of choice and its consequence are separated by time.

To give you a little introduction on this topic, take a look at this replication of the famous Marshmallow Test. The experiment proved that giving children the choice of either having one sweet immediately, or waiting a little bit longer to receive two is enough to place them in a small existential crisis.

We might be laughing but as adults many of our financial decisions can cause us a similar headache. A lot of the time, we have to decide between saving up or a quick satisfaction.

Are you going out for drinks tonight or do you want to save up for those expensive concert tickets? Do you want to renovate your house next year or book a last-minute flight to a sunny destination this summer?

To help us settle on intertemporal choices, we have to do a fair share of mental accounting, which involves discount rates. In short, our rule of thumb is: the better the ultimate pay-off is, the longer we're willing to wait for it.

If the artist performing at the concert you might be going to isn't really one of your favorites, chances are likely you'll give up your savings on something with a more proximate pay-off - like expensive cocktails at your favorite bar.

However, these discount rates are rarely based on hard logic.

Imagine I gave you the following choice:

A) I'll give you €11 per month for a period of ten months;

B) I'll give you €100 at once.

While A is the more lucrative option in the long run, most people will go for the quick buck instead - just because the joy of receiving money is much greater when it's given to you all at once, rather than spread out in small sums over a long time.

Now imagine the tables were turned. You could either give me €100 now or pay it over a period of ten months with a 10% interest rate. It may depend on the amount of money you currently have at your disposal, but in the negative condition, more people will go for the separate option.

While joy is rather experienced all at once, we'd rather break the pain of paying down into smaller bits.

Pro-tip for marketers: Offer your products in a way that accommodates your customers temporal preferences.

Arrange decoupled payment options to accommodate you customers. For expensive products or services, provide them with the option of paying a smaller amount over a longer period of time with a little interest. This should decrease their experience of negative emotions.

On the other hand, you could offer premium next-day-delivery options for those who are a little less patient. Some clients want to experience the joy of opening up their package sooner rather than later and might be willing to pay just a little bit more for it.

There you have it! The irrefutable evidence that proves there’s no such thing as a 100% rational consumer. And to be honest, let’s be glad there isn’t.

Having to keep track of all people’s little quirks and imperfections is what forces marketers and advertisers to be more empathetic and develop their creative skills.

Just think of the countless memorable campaigns we’ve seen throughout the years as a result of companies acknowledging their clients as actual people rather than numbers. So let us say once and for all: Hooray for being irrational!

To summarize your key takeaways: